One of my pet peeves is people who come up with a speculative theory about something, adopt it as fact, and militantly reject any alternative theory or interpretation. Although the phenomenon appears in a variety of settings (I certainly see quite of bit of it in attorneys' interpretation of the law), it is particularly rife in various genre fandoms, including science fiction and mystery fandoms. This may result from a fan adopting a particular work or universe as his or her own, to the point where his or her "understanding" of the work trumps not only any other interpretation, but the author's own view of the work. (My cousin Lee Goldberg, who has worked on several SF and mystery shows and who has aroused more than one fan's ire, coined the apt term "Talifans" for folks who militantly shout down opinions about their particular obsession that differs from their own.)

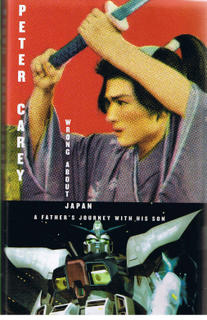

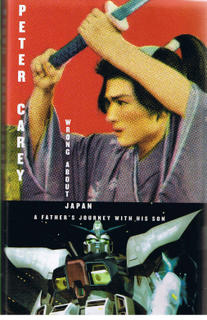

One of the subtexts of

Wrong about Japan -- a short and highly entertaining book by novelist Peter Carey -- is that tendency, which manifests both in the author and the people in Japan he meets. The foundation for the book is the author's growing fascination with Japanese animation and manga, which has beguiled his shy 12 year old son. Carey Sr., who has been to Japan before, hatches a plan to explore Japan's culture through interviews of manga creators and anime directors. He also seeks the perspective of others relevant to various significant anime works -- for instance, he watches

My Neighbor Totoro with a Japanese architect to get his perspective on the old country home that is practically a main character in that film; talks to a Japanese swordmaker to explore the nuances of

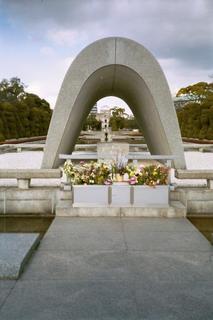

Blood, the Last Vampire; and interviews a survivor of the firebombing of Tokyo who knew the author of the novel

Grave of the Fireflies, later made into an anime film.

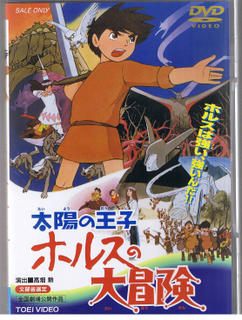

Carey has his son formulate questions for the anime interviewees, which are translated and provided to the directors and the like in advance. Time and again, Carey comes up with his own interpretations of what the filmmakers are trying to communicate in their anime works; time and again, he is informed that he is "wrong." Most memorably, he advances the theory to Yoshiyuki Tomino, the creator of the

Mobile Suit Gundam giant robot franchise, that a theme of his work is to show young people battling encased in armor, to empower the youth who are victimized by war. Tomino gently replies, through a translator, that

Gundam was a vehicle intended to sell toy robots. The various artistic choices in it were compromises intended to sell the toys better. And Tomino used young soldiers because, until the last two World Wars (and to some degree during those wars), children fought in wars.

In many cases, this is because the person he is talking to has come up with his own theory of interpretation, and attributes Carey's theories to some stereotype about Westerners, or more often Americans. Attitudes and loyalties also play a part: A Japanese youth who befriends Carey's son (and who, I later discovered, was a fictional composite character) tries to dissuade the Careys from visiting Hayao Miyazaki's Studio Ghibli, and wants them instead to visit his home and watch

Gundam videotapes. It turns out that he has pledged his obsession to

Gundam, and feels one cannot enjoy both

Gundam series and Miyazaki's works -- reminiscent of the various silly Marvel vs. DC or

Star Trek vs.

Babylon 5 rivalries that pop up amongst American fans.

In any event, Carey eventually begins to bristle, wearying of being told constantly that he is wrong about Japan. It builds to a satisfying climax that makes a point of how preconceptions and expectations can color one's experience of another culture.

This isn't the deepest book about Japan, or the anime/manga phenomenon, but it's certainly an enjoyable one.

One of my pet peeves is people who come up with a speculative theory about something, adopt it as fact, and militantly reject any alternative theory or interpretation. Although the phenomenon appears in a variety of settings (I certainly see quite of bit of it in attorneys' interpretation of the law), it is particularly rife in various genre fandoms, including science fiction and mystery fandoms. This may result from a fan adopting a particular work or universe as his or her own, to the point where his or her "understanding" of the work trumps not only any other interpretation, but the author's own view of the work. (My cousin Lee Goldberg, who has worked on several SF and mystery shows and who has aroused more than one fan's ire, coined the apt term "Talifans" for folks who militantly shout down opinions about their particular obsession that differs from their own.)

One of my pet peeves is people who come up with a speculative theory about something, adopt it as fact, and militantly reject any alternative theory or interpretation. Although the phenomenon appears in a variety of settings (I certainly see quite of bit of it in attorneys' interpretation of the law), it is particularly rife in various genre fandoms, including science fiction and mystery fandoms. This may result from a fan adopting a particular work or universe as his or her own, to the point where his or her "understanding" of the work trumps not only any other interpretation, but the author's own view of the work. (My cousin Lee Goldberg, who has worked on several SF and mystery shows and who has aroused more than one fan's ire, coined the apt term "Talifans" for folks who militantly shout down opinions about their particular obsession that differs from their own.)

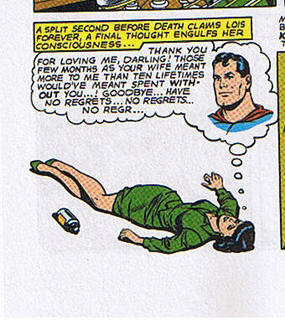

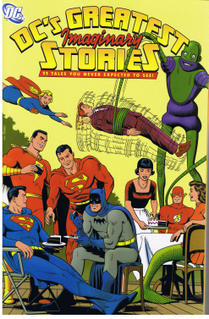

It's summertime, and the reading is easy. DC has put out another fun trade paperback of Silver Age stories. This one collects "imaginary stories." Now of course all of their superhero stories are "imaginary," in the sense that they're fictional. But these were stories where the writers would take a "what if" concept and roll with it, without any concerns about trashing characters or concepts for future stories -- because they occur "on an imaginary day which may or may not happen . . . ."

It's summertime, and the reading is easy. DC has put out another fun trade paperback of Silver Age stories. This one collects "imaginary stories." Now of course all of their superhero stories are "imaginary," in the sense that they're fictional. But these were stories where the writers would take a "what if" concept and roll with it, without any concerns about trashing characters or concepts for future stories -- because they occur "on an imaginary day which may or may not happen . . . ."